Graham Greene: Doubter Par Excellence

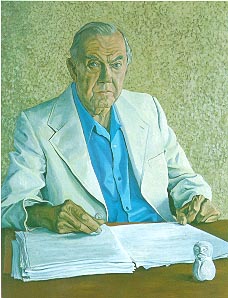

Graham Greene (1904-1991)

Graham Greene (1904-1991)

by Anthony Palliser

|

by JOSEPH PEARCE

Graham Greene is perhaps the

most perplexing of all the literary converts whose works animated

the Catholic literary revival in the 20th century. His visions

of angst and guilt, informed and sometimes deformed by a deeply

felt religious sensibility, make his novels, and the characters

that adorn them, both fascinating and unforgettable.

His fiction is gripping because it grapples with faith and disillusionment

on the shifting sands of uncertainty in a relativistic age. His

tormented characters are the products of Greene's own tortured

soul, and one suspects that he was more baffled than anyone else

at the contradictions at the core of his own character and, in

consequence, at the heart of the characters that his fertile

and fetid imagination had created.

From his earliest childhood Greene exhibited a world-weariness

that at times reached the brink of despair. In large part this

bleak approach may have been due to a wretched childhood and

to the traumatic time spent at Berkhhamsted School where his

father was headmaster. His writing is full of the bitter scars

of his school days. In his autobiographical A

Sort of Life ,

Greene described the panic in his family after he had been finally

driven in desperation to run away from the horrors of the school:

"My father found the situation beyond him . . . My brother

suggested psychoanalysis as a possible solution, and my father

- an astonishing thing in 1920 - agreed." ,

Greene described the panic in his family after he had been finally

driven in desperation to run away from the horrors of the school:

"My father found the situation beyond him . . . My brother

suggested psychoanalysis as a possible solution, and my father

- an astonishing thing in 1920 - agreed."

For six months the young, and no doubt impressionable, Greene

lived at the house of the analyst to whom he had been referred.

This episode would be described by him as "perhaps the happiest

six months of my life," but it is possible that the seeds

of his almost obsessive self-analysis were sown at this time.

Significantly, he chose the following words of Sir Thomas Browne

as an epigraph to his first novel, The

Man Within :

"There's another man within me that's angry with me." :

"There's another man within me that's angry with me."

In later years, the genuine groping for religious truth in Greene's

fiction would often be thwarted by his obsession with the darker

recesses of his own character. This darker side is invariably

transposed onto all his fictional characters, so that even their

goodness is warped. Greene saw human nature as "not black

and white" but "black and grey," and he referred

to his need to write as "a neurosis . . . an irresistible

urge to pinch the abscess which grows periodically in order to

squeeze out all the pus." Such a tortured outlook may have

produced entertaining novels but could not produce any true sense

of reality. Greene's novels were Frankenstein monsters that were

not so much in need of Freudian analysis as the products of it.

Greene's conversion in 1926, when he was still only 21 years

old, was described in A

Sort of Life ,

in which he contrasted his own agnosticism as an undergraduate,

when "to me religion went no deeper than the sentimental

hymns in the school chapel," with the fact that his future

wife was a Roman Catholic: ,

in which he contrasted his own agnosticism as an undergraduate,

when "to me religion went no deeper than the sentimental

hymns in the school chapel," with the fact that his future

wife was a Roman Catholic:

I met the girl I was to marry after finding a note from her at

the porter's lodge in Balliol protesting against my inaccuracy

in writing, during the course of a film review, of the "worship"

Roman Catholics gave to the Virgin Mary, when I should have used

the term "hyperdulia." I was interested that anyone

took these subtle distinctions of an unbelievable theology seriously,

and we became acquainted.

The girl was Vivien Dayrell-Browning, then 20 years old, who,

five years earlier, had shocked her family by being received

into the Catholic Church. Concerning Greene's conversion, Vivien

recalled that "he was mentally converted; logically, it

seemed to him . . . It was all rather private and quiet. I don't

think there was any emotion involved." This was corroborated

by Greene himself when he stated in an interview that "my

conversion was not in the least an emotional affair. It was purely

intellectual."

A more detailed, though hardly a more emotional, description

of the process of his conversion was given in his autobiography.

"Now it occurred to me . . . that if I were to marry a Catholic

I ought at least to learn the nature and limits of the beliefs

she held." He walked to the local "sooty neo-Gothic

Cathedral" which "possessed for me a certain gloomy

power because it represented the inconceivable and the incredible"

and dropped a note requesting instruction into a wooden box for

enquiries. His motivation was one of morbid curiosity and had

precious little to do with a genuine desire for conversion. "I

had no intention of being received into the Church. For such

a thing to happen I would need to be convinced of its truth and

that was not even a remote possibility."

His first impressions of Fr. Trollope, the priest to whom he

would go for instruction, had reinforced his prejudiced view

of Catholicism: "At the first sight he was all I detested

most in my private image of the Church." Soon, however,

he was forced to modify his view, coming to realize that his

initial impressions of the priest were not only erroneous but

that he was "facing the challenge of an inexplicable goodness."

From the outset he had "cheated" Fr. Trollope by failing

to disclose his irreligious motive in seeking instruction, nor

did he tell the priest of his engagement to a Catholic. "I

began to fear that he would distrust the genuineness of my conversion

if it so happened that I chose to be received, for after a few

weeks of serious argument the 'if' was becoming less and less

improbable."

The "if" revolved primarily on the primary "if"

surrounding God's existence. The center of the argument was the

center itself or, more precisely, whether there was any center:

My primary difficulty was to believe in a God at all . . . I

didn't disbelieve in Christ - I disbelieved in God. If I were

ever to be convinced in even the remote possibility of a supreme,

omnipotent and omniscient power I realized that nothing afterwards

could seem impossible. It was on the ground of dogmatic atheism

that I fought and fought hard. It was like a fight for personal

survival.

The fight for personal survival

was lost and Greene, in losing himself, had gained the faith.

Yet the dogmatic atheist was only overpowered; he was not utterly

vanquished. He would reemerge continually as the devil, or at

least as the devil's advocate, in the murkier moments in his

novels.

The literary critic, J.C. Whitehouse, has compared Greene to

Thomas Hardy, rightly asserting that Greene's gloomy vision at

least allows for a light beyond the darkness, whereas Hardy allows

for darkness only. Chesterton said of Hardy that he was like

the village atheist brooding over the village idiot. Greene is

often like a self-loathing skeptic brooding over himself. As

such the vision of the divine in his fiction is often thwarted

by the self-erected barriers of his own ego. Only rarely does

the glimmer of God's light penetrate the chinks in the armour,

entering like a vertical shaft of hope to exorcise the simmering

despair.

Few have understood Greene

better than his friend Malcolm Muggeridge, who described him

as "a Jekyll and Hyde character, who has not succeeded in

fusing the two sides of himself into any kind of harmony."

There is more true depth and perception in this one succinct

observation by Muggeridge than in all the pages of psycho-babble

that have been written about Greene's work by lesser critics.

The paradoxical union of Catholicism and skepticism, incarnated

in Greene and his work, had created a hybrid, a metaphysical

mutant, as fascinating as Jekyll and Hyde and perhaps as futile.

The resulting contortions and contradictions of both his own

character and those of the characters he created give the impression

of depth; but the depth was often only that of ditch water, perceived

as bottomless because the bottom could not be seen. Greene's

genius was rooted in the ingenuity with which he muddied the

waters.

It was both apt and prophetic

that Greene should have taken the name of St. Thomas the Doubter

at his reception into the Church in February 1926. Whatever else

he was or wasn't, he was always a doubter par excellence.

He doubted others; he doubted himself; he doubted God. Ironically,

it was this very doubt that so often provided the creative force

for his fiction. Perhaps the secret of his enduring popularity

lies in his being a doubting Thomas in an age of doubt. As such,

Greene's Catholicism becomes an enigma, a conversation piece

- even a gimmick. Yet if his novels owe a debt to doubt, their

profundity lies in the ultimate doubt about the doubt. In the

end this ultimate doubt about doubt kept Graham Greene clinging

doggedly, desperately - and doubtfully - to his faith.

-------------------------------------

This article is reprinted with permission from Lay

Witness magazine. Lay

Witness is a publication of Catholic United for the Faith,

Inc., an international lay apostolate founded in 1968 to support,

defend, and advance the efforts of the teaching Church.

|